The Effective School Owner: 5 Leadership Strategies for Women

After 24 years as a K-College teacher and administrator, I ventured into the new space of preschool ownership in 2018. I eased into the new role by first surveying the logistics and culture of the school. During my assessment mode, I jumped in fully and started to plunge toilets, wipe babies, coach teachers, and support parents.

From Busy-Ness to Business

By the end of the first year, the school hummed along like a finely tuned machine. I put in 15 hour days of sweat equity, but my profits were quite paltry. I realized that I had tremendous passion and skill on the school operations side, but needed tools as a business leader as well.

Eventually, I discovered The Effective Executive by Peter Drucker. Drucker offers instructions to executives on moving away from busy-ness and into effective business management.

Originally published in 1964, the book’s male-centric vantage point reads like something from the TV show Mad Men, but it contains valuable lessons for men and women. The first chapter “Effectiveness Can Be Learned” offers terrific insight that I used to reduce my 15 hour days and transform my busy-ness into more productive, profitable, and sustainable business management.

The Challenges Facing Our Preschools

Usually, working in child care can be economically tenuous, but the pandemic of 2020 starkly exposed the economic fragility of the industry, especially for women. Of the roughly two million adults in the field of early childhood education, 40 percent are women of color. Almost 77 percent of people in early childhood education earn less than $15 per hour, an amount widely regarded as a living wage.

Owners may find ourselves working as owners and teachers, owners and directors, or owners and administrators to fill gaps left by teachers fleeing early childhood education work in favor of better pay.

These factors make it difficult for preschool leaders to have the time to consider fiduciary moves that will benefit the long-term life of our schools.

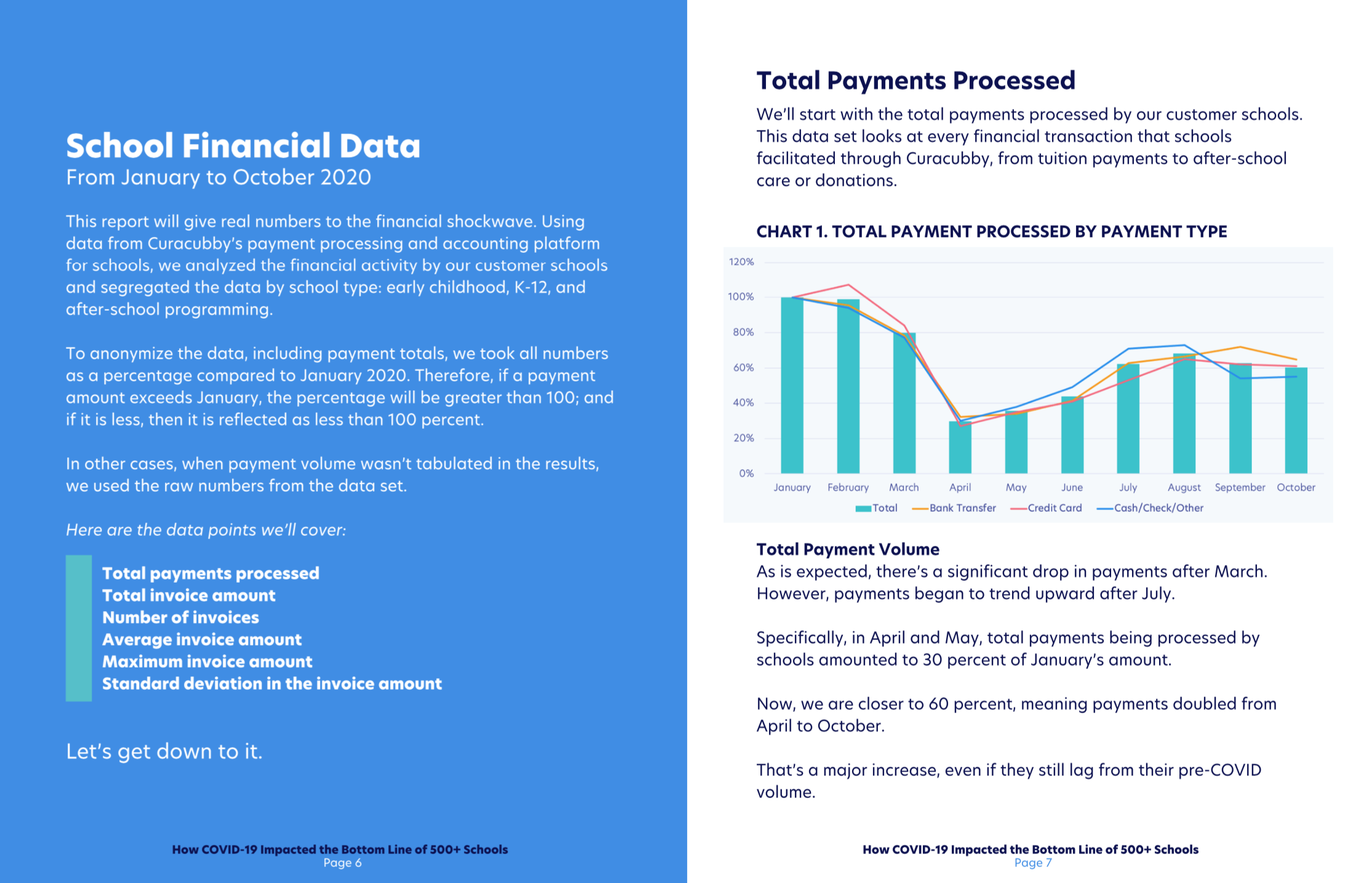

During the pandemic of 2020, the Bipartisan Policy Center reported that 60 percent of licensed providers closed and many reduced capacity or hours. The challenge of staying financially viable in those circumstances is clear considering data from The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC).

Only 11 percent of providers could survive a closure of an indeterminate length of time without government support—and only 27 percent could close for one month. We witnessed this cruel reality as schools thriving with active days and happy communities suddenly closed for good. In very short order, the economic reality collided with the false security provided by a happy existence.

Confronting These Challenges With Leadership

The rapid decline points to a need to become better executives and owners. At the epicenter of Drucker’s thesis is the person at the helm of the whole operation: the executive. We know that person as the school owner. It’s easy to forget the ‘owner’ part of the owner/director or owner/administrator identities, but focusing on nurturing that identity could be the difference in the survival of a preschool.

My first epiphany with Drucker’s book started after reading that the effective executive “is expected to get the right things done.” I was stunned to realize I had missed some of the right things during all my long days. Many of us do this as we plow through our endless To-Do Lists.

Are we using our expertise and savvy for growth? How much of our time is being spent on each of our identities? As mom? As teacher? As director? As owner? As spouse?

Women frequently find themselves wearing multiple hats at work and just as many at home. How do we design a hat that specifically suits and grows our business?

The Female School Leader

Before any progress can be made, time must be allocated to thinking about, planning, and executing those goals. This presents one of the biggest hurdles given that the basic day-to-day needs of a school often demand more attention and hours than we can muster.

The Female School Leader often has to make tough choices for her time...

She may work through lunch to make time for a conversation with unhappy parents or the occasionally unreasonable representatives from licensing agencies.

She has to work magic to steal hours to attend much needed professional developments only to find that there’s no time for implementing what has been learned.

These are choices about spending time, but – and here’s the hard part – some of these must be handed off to allow for the right things.

The Female Leader, as it turns out, is like anyone else in business leadership. Drucker describes the quandary leaders, or Knowledge Workers, as the Realities of the Executive. For our purposes, these four realities are in the context of running school in tandem with personal lives and households.

If we replace ‘executive’ and with ‘school owner’, his Executive Realities may ring a very familiar bell. Specifically:

- The school owner’s time tends to belong to everybody else.

- School owners are forced to keep on ‘operating’ unless they take positive action to change the reality in which they live and work.

- The third reality pushing the school owner toward ineffectiveness is that she is within an organization. This means that she is effective only if and when other people make use of what she contributes.

- Finally, the school owner is within the organization...She sees the outside only through thick and distorting lenses if at all.

Drucker accurately suggests that “the center of gravity has shifted to the knowledge worker, the man who puts to work what he has between his ears rather than the brawn of his muscles or the skill of his hands.”

But the time for using what’s between our ears doesn’t come easily. Time spent thinking seems unproductive, yet, effective planning cannot happen without clustered, sacred moments devoted considering strategy development and execution.

The Five Habits of Mind for School Owners

Drucker suggests five practices, or Habits of the Mind, that the Female School Leader can adopt to get the right things done. She must make it a priority to:

- Know exactly where her time goes.

- Focus more attention on contributions outside of her school.

- Survey her staff, then build on their strengths.

- Identify, then work to develop only one or two areas of her center’s superior performance which produces outstanding results.

- Spend the time needed to make effective decisions.

These Habits of Mind may require a significant amount of devotion, discipline, and purpose, but they are game-changers. Here are some ways to more easily incorporate these changes into a daily routine.

How-To #1: Know Where Your Time Goes

Start with a task for self-reflection to get an accurate sense of your use of time. Create a Time Inventory that lists every single hour of every day for 3-5 days. Include a day on the weekend, writing every activity you have done for those days.

After creating the Time Inventory, ask yourself these questions for reflection:

- How many hours have I devoted to financial planning for my school?

- How many hours have I devoted to innovations that will make my school stand out in a field crammed with other schools, some of which are free?

- Which daily tasks am I doing that can be done by someone else?

- Which tasks can only be done by me?

At the end of your recording and reflection, edit out time wasters. Replace time-wasters with thinking time, and then record thoughts in a journal. I use a journal that says, “You’re Awesome” on the outside to remind me that the ideas inside are awesome, too.

How-To #2: Focus on Outward Contributions

Each county and state has a set of organizations focused on preschool improvement. Joining one of these organizations essentially commits your preschool or private school-age programs to evaluation.

Admittedly, an evaluation may sound intimidating, but evaluation adds an outsider's perspective for school improvements. Joining local organizations associated with Quality Improvement Rating Systems (QIRS) work to improve programs through non-punitive incentives and coaching.

School leaders may also access locally SBA-sponsored women’s business centers. Their free or low-cost courses help develop skills for running successful businesses.

Joining such organizations definitely takes up time, but the commitment elbows space in crowded schedules for the things that will actively build your program and business.

How-To #3: Build On Strengths

Because thinking time is crucial, meetings with staff offer time for imagining. Ask teachers and staff to imagine using their best skills, favorite hobby, or talent at the school. Ask them to describe a lesson they would present if they could use the skill, talent, or hobby with your school’s children, parents, or teachers.

How would they put this skill, talent, or favorite hobby to use if they could do it long or short term?

This conversation will help you discover more about your team and give you some ideas for new programs that can be implemented with existing staff. If you have an avid baker, why not offer baking classes after school hours? If you have a person who really loves scrapbooking, why not offer a low-cost scrapbooking class to parents one weekend?

Using the strengths of your staff will only make your school stronger, more unique, and more interesting.

How-To #4: Focus on Few Major Areas, One at a Time

This may prove most difficult for school leaders. We sometimes complain about all of our hats, but we won’t put one or two on the hat rack. Instead of doing everything, take inventory of the things you’re best at and concentrate improvement efforts on one or two areas of your strength at a time.

These priorities can be developed collaboratively with your staff. They know the school and they know you. They will be able to offer some insight on your strengths and where best to use your energy.

As a formal or informal exercise, query the staff about your strengths. It can be humbling to hear how folks really feel, but getting a good perspective on your capacity helps you focus your talents and strengths. For those who are a bit nervous about getting such feedback, doing a self-reflection with the same questions may prove just as efficacious.

Concentrate on your real, true strengths of talent and spirit. Ask: What am I most passionate about in regards to the curriculum, economics, or operations of my school? What has been my most successful experiences with the program? What have I done that has made the biggest positive change in my school? Why did it work so well?

After spending some time thinking of what drives you and what you do well, build SMART Goals to extend the progress you have already made.

How-To #5: Spend Time to Make Truly Effective Decisions

My school/company uses a circuitous process that includes people who will have a stake in the impact of the decisions being made. I cannot do all of the jobs in my center myself, so it makes sense to include the people who will have some level of responsibility for maintaining that particular area.

For example, I don’t make decisions about a food program without the cook. I don’t make decisions about enrollment without my enrollment administrator, and so on.

We use a simple, but effective process for making decisions and taking action.

- Identify the people who will have the day-to-day responsibility for doing the work needed for change.

- Evaluate the situation. Collectively, decide the primary problem that needs to be addressed or innovation that needs to be implemented.

- Gather data about the problem or idea and its pros and cons. This may be anecdotal data or quantitative data.

- Brainstorm solutions based on the data. At this stage, pretty much any idea has merit. This isn’t the stage for questions about the budget or the things that will stimy brainstorming.

- Make a practical plan. Usually, one idea simmers to the top of discussions. The prevailing idea will need a plan of action that details who will do it, how they will do it, what they will need, and a definitive date on when you will all check in on progress.

Then, when you check-in on progress, restart the process at #1 and focus on the things that are working and how to continue to make these things work even better.

A Greater Impact

Make no mistake, becoming an effective school leader requires deliberate, but necessary action for growth in business. Although these steps are not a guarantee that your business will suddenly turn profitable, these steps offer a structure to create a plan for your particular context and staff.

It may take some time to shift into a more effective environment, but doing so is imperative for business growth. The rest of The Effective Executive offers great insight on productivity and offers several stories of the right and wrong way to strengthen the work environment.

Preschool leaders may have a particular set of circumstances, but there is priceless value in recognizing that at the end of the day, a privately-owned preschool is a business. Focusing on school leadership really shifts thinking away from daily tasks and into thinking about a long, impactful, sustainable and financially stable life with your school.

Jennifer Carter is the Executive Director of Oak Tree Learning Center in San Bernardino, California.